From communities displaced by fierce floods in East Africa and Spain, to record-breaking drought in the Amazon, 2024 has demonstrated the vulnerabilities of communities all over the world.

The UAE Global Framework for Climate Resilience and the Global Goal on Adaptation (also known as the GGA) aim to protect communities from the worst impacts of climate change. A critical component of the Framework is ensuring water and sanitation systems are equipped to withstand the shocks of a changing climate.

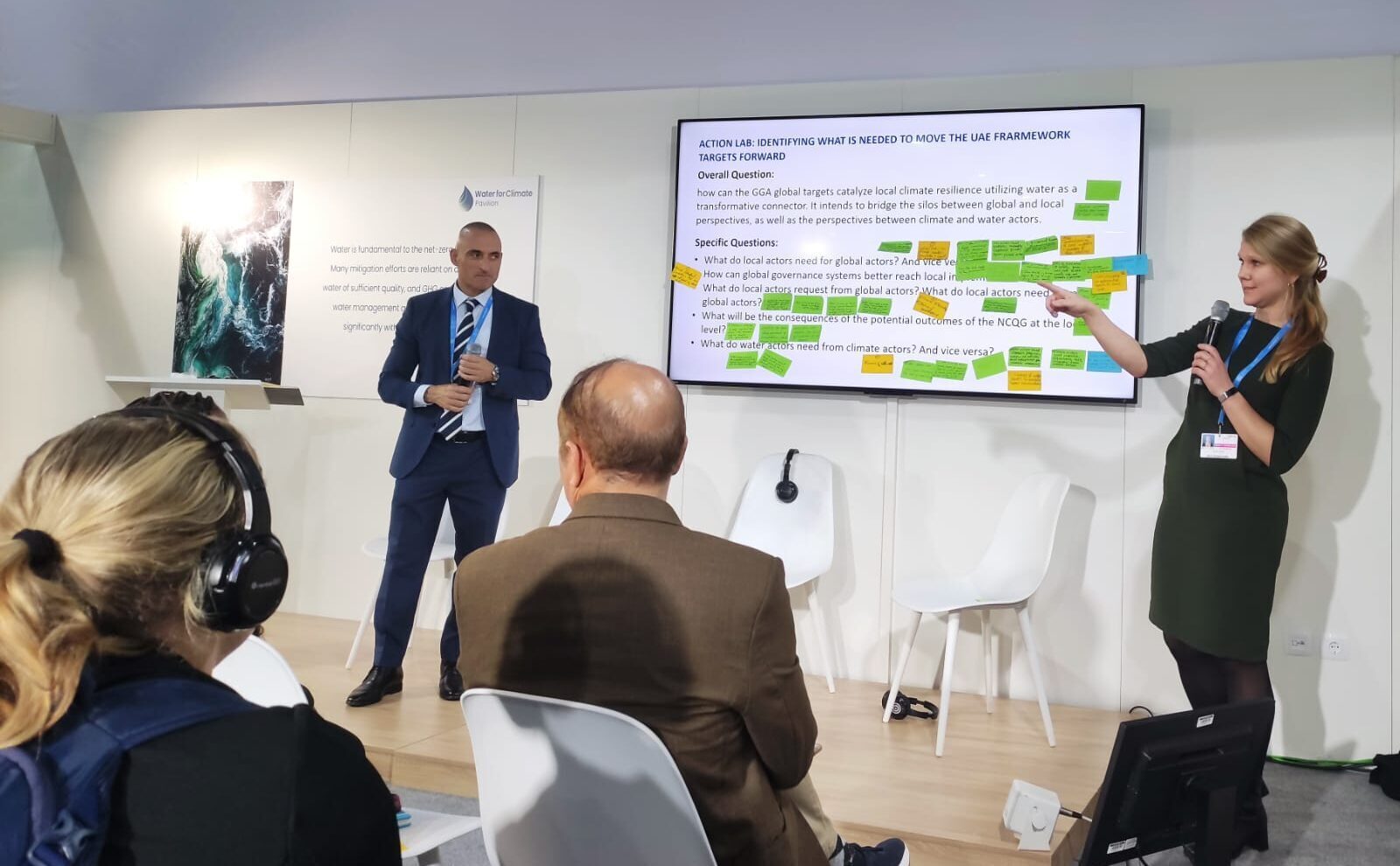

At COP29, negotiators are grappling with one of the most challenging aspects of the Global Goal on Adaptation: defining measurable indicators for adaptation progress. With nearly 9,000 potential indicators proposed, negotiators face a Herculean task to whittle down to those that are both meaningful and feasible. They also need to avoid placing undue reporting burdens on nations already stretched thin.

José Gesti, Water for Climate Pavilion Envoy on the Global Goal on Adaptation and Senior Climate Advisor at Sanitation and Water for All (SWA), has been actively involved in these discussions, particularly regarding water-related indicators. In an interview, he shared insights on the discussions at COP29 and outlined what lies ahead in advancing these critical adaptation efforts.

Where did the idea for the Global Goal on Adaptation come from?

The Global Goal on Adaptation originates from Article 7 of the Paris Agreement, which calls for enhancing adaptive capacity, strengthening resilience and reducing vulnerability to climate change. Adaptation means that we recognize that climate change is having adverse effects on our planet, and will continue to do so. Therefore, we need to take action to prevent or minimize climate impacts. Nearly every country in the world is a party to the Paris Agreement, and they send negotiation teams to COP to hammer out global climate policy.

For people not in the policy space, what are targets and indicators and how do these translate into climate policies in our own countries and communities?

That’s a key question we’re asking at COP29: how do we convert something as high level as a COP framework into reality on the ground?

Targets and indicators are essentially tools to measure and guide progress. Targets define the goals we want to achieve and when we want to achieve them by — for example, reducing water scarcity and enhancing global resilience to floods, droughts, heatwaves, and rising sea levels by 2030. Or ensuring we have climate-resilient water and sanitation systems by 2030. Indicators, on the other hand, are the metrics we use to track whether we’re meeting those targets. For example, an indicator might measure the percentage of a population with access to drinking water during a drought.

At the global level, these targets and indicators give us a shared framework—a common language—for tackling climate adaptation. This has to now translate into national policies and it has to cascade down as soon as possible into local action.

For instance, a country might take a global target on water resilience and develop local policies to upgrade water infrastructure, implement conservation programs, or create early warning systems for droughts. These actions are tailored to local conditions and needs, but the new framework will enable us to assess global progress toward adaptation by aggregating and summing up local progress.